GDPR – now as a poetry collection

Much of the discussion about GDPR has revolved around how companies can become compliant and avoid fines. But what do the new EU rules on data protection really mean for us as individuals? Two ITU researchers encourage us to reflect on the consequences of GDPR with a new collection of poems based on the legal document itself.

Business IT Departmentprivacybig datadigital artRachel Douglas-JonesMarisa Cohn

Written 19 February, 2019 07:04 by Vibeke Arildsen

In the spring of 2018, our inboxes were suddenly flooded with emails from companies about personal data and consent. The occasion was, of course, the new EU Data Protection Regulation – or GDPR – coming into effect on May 25.

At ITU's ETHOS Lab, GDPR was celebrated with a ‘Great Deletion Poetry Rave’. With the windows sealed off and all 260 legally dense pages of the regulation hung up on the walls, 50 researchers from ITU and other Danish universities started transforming the legal document into poetry by erasing its words. A similar event took place at the ETHOX Center at Oxford University.

Twenty of the poems that came out of these events have now been published in the poetry collection GDPR: Deletion Poems, edited by Rachel Douglas-Jones and Marisa Cohn, both researchers at ITU. The idea is to provide a new tool for studying the regulation and get us thinking about what our new rights really mean, says Rachel Douglas-Jones.

"In connection with the introduction of GDPR, we all received mails from companies wanting us to confirm newsletter subscriptions or inform us of our right to be deleted. It was all about compliance for companies,” she says.

GDPR is written in a very inaccessible, legal language and there are not many initiatives that allow people to understand the new rights that the regulation offers. The deletion poems are a way to approach the document in a playful and reflective way.

Rachel Douglas-Jones, Associate Professor at ITU

"However, GDPR is written in a very inaccessible, legal language and there are not many initiatives that allow people to understand the new rights that the regulation offers. The deletion poems are a way to approach the document in a playful and reflective way. ”

Erasure as protest

The method of creating poems by erasing bits of a text is called ‘erasure poetry’ and has previously been used by Chinese-British poet Sarah Howe and a wave of American poets in the wake of Donald Trump's inauguration as president.

"Erasure poetry is a good way of capturing or highlighting a central theme in a text, and it is often used as a kind of protest. So you can also see this as a way of protesting the inaccessibility of the GDPR. It is so inaccessible that it is necessary to delete 90 percent of the text before it makes sense," says Rachel Douglas-Jones.

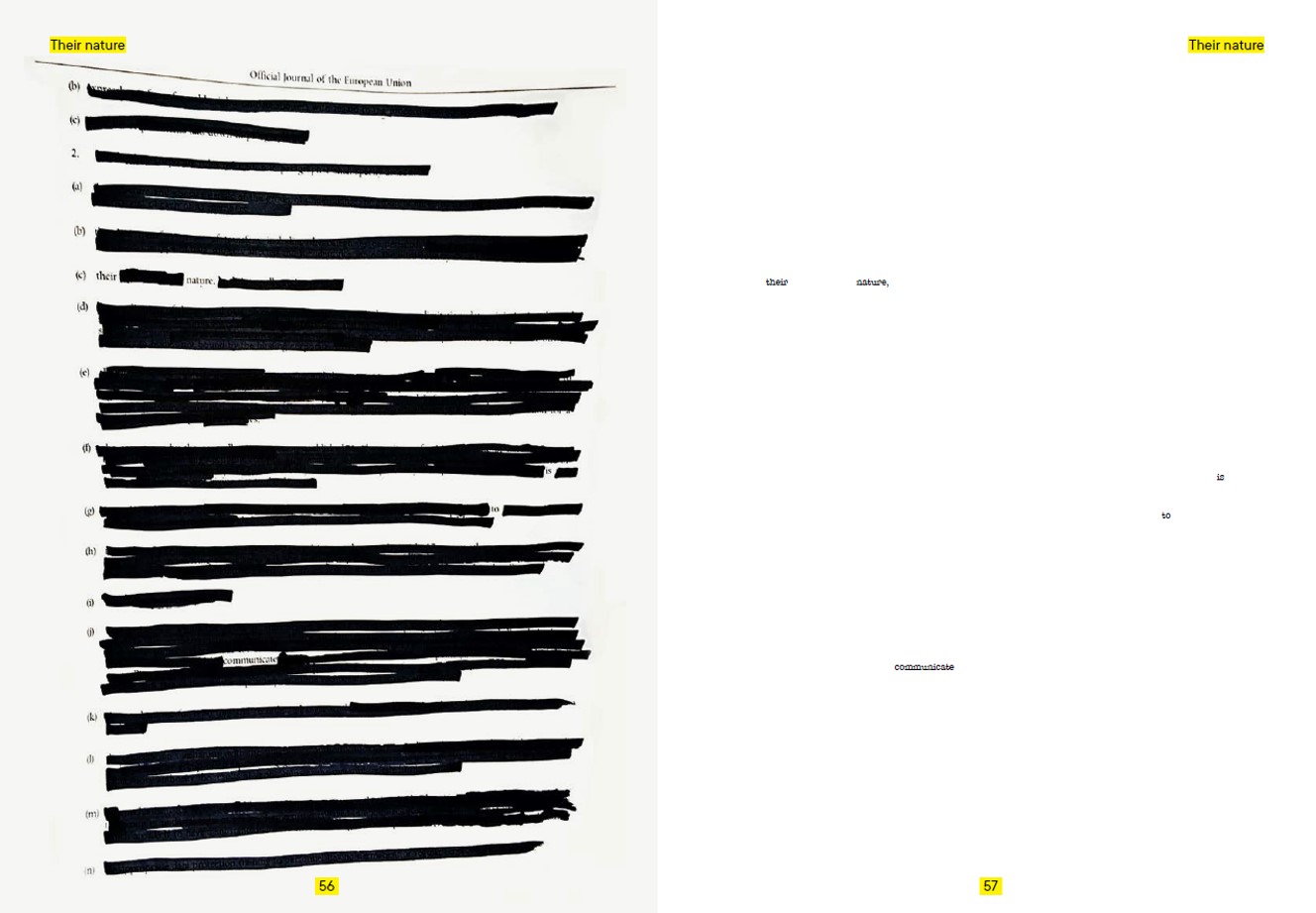

"Their nature is to communicate". The process of immersing oneself in the GDPR text and deciding which new meaning you want to create takes time. This poem, which is one of the shortest in the collection, took 45 minutes to create. The author is an anonymous participant at the GDPR rave in Oxford.

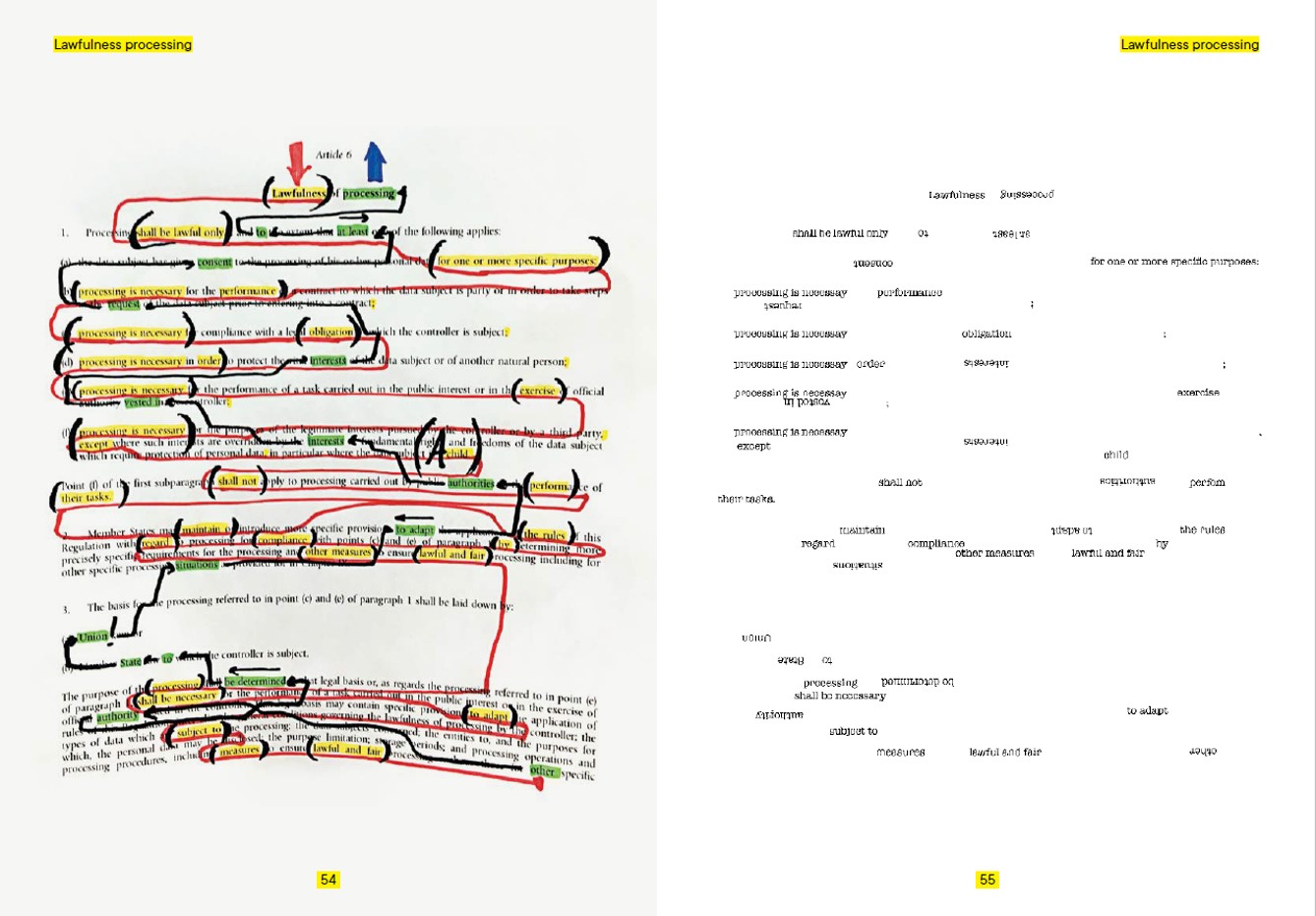

"Lawfulness Processing", one of the most creative GDPR poems, can be read forwards or backwards (anonymous author).

A tool for reflection

Despite the complexity of the GDPR, Rachel Douglas-Jones thinks it is highly relevant for ordinary people to dive into the regulation and reflect on what it means to them personally.

"GDPR changes the basic rights we have in terms of data protection in Europe. It gives you the right to ask for information that is being held about you and to have information deleted - rights that weren’t previously there. They are important because they increase the rights of appeal that individuals have on the processing and use of their data, especially in cases where decisions are being made on the basis of that data,” she says.

She hopes that the poems will be used to start discussions on data protection and rights, for example in high schools and universities.

"The poems can be used as an teaching tool to give students a completely different perspective on what GDPR is and then afterwards think about who the ‘data controller’ is. How do you find a data controller that has data about you, how do you contact them, and how long might it take before you hear back from them?”

On the last pages of the book, readers have the opportunity to create their very own GDPR poem. Rachel Douglas-Jones, Associate Professor, phone +45 7218 5058, email rdoj@itu.dk

Vibeke Arildsen, Press Officer, phone 2555 0447, email viar@itu.dk