Study: Female researchers rival men in productivity – but have shorter careers

A comprehensive study of the careers of 1.5 million researchers shows that women and men on average produce the same number of scientific articles annually, but that women tend to leave their research careers earlier. According to ITU researcher Roberta Sinatra, co-author of the study, the study should inspire decision-makers to take a closer look at the reasons why women leave academia.

Computer Science DepartmentResearchdata sciencediversityRoberta Sinatra

Written 30 November, 2020 08:33 by Vibeke Arildsen

It is well documented that female researchers, on average, produce fewer scientific articles and obtain fewer citations during their careers than their male colleagues.

Now, a study of more than 1.5 million research careers that ended between 1955 and 2010 provides a quantitative mapping of the gender differences – and a simple explanation for them.

Same productivity, but shorter careers

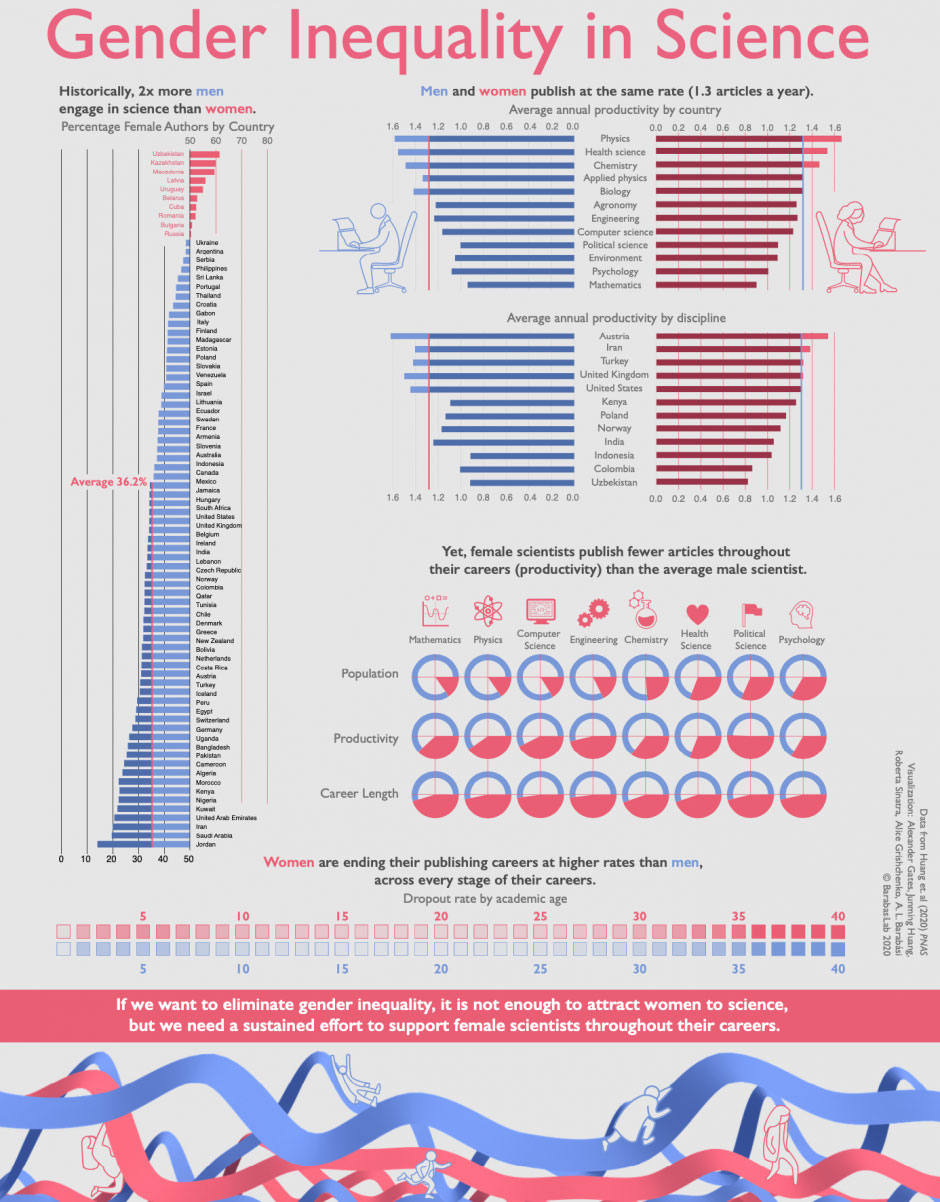

The study shows that women and men are equally productive when controlling for career length. Women produced an average of 1.33 and men 1.32 scientific articles per year and had similar impact, measured by number of citations.

The explanation for the lower number of articles and citations produced by women can first and foremost be found in the fact that their research careers are shorter: on average, women's publishing careers lasted 9.3 years, compared with 11 years for men.

See some of the findings of the study in the infographic above.

Looking at the Danish figures, the gender differences are even more pronounced. Here, the women's career lengths averages at 11.28 years and the men's 14.51 years - which gives male researchers 3 more years to produce scientific articles and accumulate citations. In Denmark, too, annual productivity is comparable with 1.37 articles for men and 1.28 articles for women.

The fact that women and men within the same fields have a comparable annual productivity tells us what is at the root of gender inequality – the fact that women tend to leave academia earlier than men.

Roberta Sinatra, Associate Professor in Data Science at ITU

"The fact that women and men within the same fields have a comparable annual productivity tells us what is at the root of gender inequality – the fact that women tend to leave academia earlier than men," says Roberta Sinatra, an Associate Professor in Data Science at the IT University of Copenhagen and co-author of the study.

Thus, the study dispels the myth that women are ‘less good’ researchers than men, or that women's obligations in relation to children and domestic chores reduce their productivity.

A general picture of inequality

Roberta Sinatra is a researcher in Data Science at ITU's Computer Science Department.What is new about the sizable analysis of more than a century’s publishing careers within STEM and social sciences is, according to Roberta Sinatra, the rigorous quantitative and systematic approach to the issue of gender inequality.

Roberta Sinatra is a researcher in Data Science at ITU's Computer Science Department.What is new about the sizable analysis of more than a century’s publishing careers within STEM and social sciences is, according to Roberta Sinatra, the rigorous quantitative and systematic approach to the issue of gender inequality.

“Until now, we have not had a good, numbers-based understanding of what drives the huge quantitative differences in how the research careers of men and women develop. The problem has mostly been investigated through qualitative studies or through smaller studies of limited groups. Here, we have had the opportunity to work systematically with a huge data set with publications from around the world, from a wide range of disciplines, and with a large time span. This is valuable because it gives us a general picture that gender inequalities exist everywhere, but at a different extent. The innovation here is that we can quantify similarities and differences between disciplines, countries and over time,” she says.

Focus needed on why women drop out

Because of the general nature of these gender inequalities, decision-makers in academia should investigate why women drop out, and create initiatives to retain them, says Roberta Sinatra.

"I definitely think we have to do something. Greater diversity and inclusion mean that we can draw on more resources and more talent,” she says.

She emphasizes that it is important not to limit the focus to the youngest group of female researchers, the PhDs. One of the study’s most important insights is that women are at greater risk of dropping out of the research world at all career levels.

Each year, on average 11% of women leave academia for good, as opposed to only 9% of men. This drop-out difference exists at all career levels and is most pronounced six years after a career start, when women are 50% more likely than men to leave academia.

The difference in the drop-out rates shows us that there are factors that make an academic career less sustainable for women. That is why a sustained effort is needed to support them throughout their careers.

“The difference in the drop-out rates shows us that there are factors that make an academic career less sustainable for women. That is why a sustained effort is needed to support them throughout their careers,” said Roberta Sinatra.

Structures reinforce inequality

Roberta Sinatra also believes that the study provides an opportunity to look at structures that may reinforce gender inequality.

“We have to be very careful how we evaluate performance and make decisions about promotions. We must be aware that there are these gender-based differences, which have nothing to do with quality, but which can lead to inequality in the assessment of men and women,” she says.

She mentions the Danish system of PP-points as an example. Here, researchers are assessed, among other things, based on how many scientific articles they publish.

We risk reinforcing inequality because we make decisions based on the already existing inequalities, which should not be there.

“We risk reinforcing inequality because we make decisions based on the already existing inequalities, which should not be there. If a woman systematically publishes fewer papers, she gets fewer points and may miss out on a promotion. This may lead to lower motivation and perhaps eventually to her choosing to drop out of academia,” she says.

The same problem applies in relation to Google Scholar, a platform where scientists obtain a rating based on parameters such as number of articles and citations.

The point is that we risk missing out on the next Marie Curie because she may have published fewer articles than Albert Einstein

“The more articles you publish, the more references and the more media coverage you get. But these indicators say nothing about quality. The point is that we risk missing out on the next Marie Curie because she may have published fewer articles than Albert Einstein,” says Roberta Sinatra.

Roberta Sinatra has just received the prestigious Sapere Aude grant from the Independent Research Fund Denmark for the project ‘Mechanistic Models for Fair Science’. In this project, she will design and develop mathematical models to support a fair comparison of researchers and research. Read more here.

Roberta Sinatra, Associate Professor, email rsin@itu.dk

Vibeke Arildsen, Press Officer, phone 2555 0447, email viar@itu.dk